3 Main Types of Motion and Kinematic Arts Movies

Naum Gabo, Kinetic Construction, also titled Standing Wave (1919–20)

Kinetic art is art from whatever medium that contains motion perceivable by the viewer or that depends on motion for its consequence. Canvas paintings that extend the viewer'south perspective of the artwork and incorporate multidimensional movement are the earliest examples of kinetic art.[1] More pertinently speaking, kinetic art is a term that today most oft refers to 3-dimensional sculptures and figures such every bit mobiles that motility naturally or are machine operated (encounter e. yard. videos on this page of works of George Rickey, Uli Aschenborn and Sarnikoff). The moving parts are generally powered by air current, a motor[2] or the observer. Kinetic art encompasses a broad diversity of overlapping techniques and styles.

There is too a portion of kinetic fine art that includes virtual movement, or rather movement perceived from just certain angles or sections of the work. This term also clashes frequently with the term "credible motion", which many people apply when referring to an artwork whose motion is created by motors, machines, or electrically powered systems. Both credible and virtual movement are styles of kinetic art that only recently have been argued as styles of op art.[3] The amount of overlap between kinetic and op art is not significant plenty for artists and fine art historians to consider merging the 2 styles under one umbrella term, but at that place are distinctions that accept notwithstanding to exist made.

"Kinetic art" as a moniker adult from a number of sources. Kinetic art has its origins in the belatedly 19th century impressionist artists such as Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Édouard Manet who originally experimented with accentuating the motility of human being figures on canvas. This triumvirate of impressionist painters all sought to create art that was more lifelike than their contemporaries. Degas' dancer and racehorse portraits are examples of what he believed to exist "photographic realism";.[4] During the late 19th century artists such every bit Degas felt the demand to challenge the movement toward photography with vivid, cadenced landscapes and portraits.

By the early on 1900s, sure artists grew closer and closer to ascribing their art to dynamic motion. Naum Gabo, one of the two artists attributed to naming this manner, wrote frequently virtually his piece of work equally examples of "kinetic rhythm".[5] He felt that his moving sculpture Kinetic Construction (also dubbed Standing Wave, 1919–twenty)[6] was the first of its kind in the 20th century. From the 1920s until the 1960s, the style of kinetic art was reshaped by a number of other artists who experimented with mobiles and new forms of sculpture.

Origins and early on development [edit]

The strides made by artists to "elevator the figures and scenery off the folio and prove undeniably that art is not rigid" (Calder, 1954)[4] took significant innovations and changes in compositional manner. Édouard Manet, Edgar Degas, and Claude Monet were the three artists of the 19th century that initiated those changes in the Impressionist move. Even though they each took unique approaches to incorporating motility in their works, they did so with the intention of being a realist. In the same menstruation, Auguste Rodin was an artist whose early on works spoke in support of the developing kinetic movement in fine art. All the same, Auguste Rodin's afterward criticisms of the move indirectly challenged the abilities of Manet, Degas, and Monet, challenge that it is incommunicable to exactly capture a moment in time and give information technology the vitality that is seen in existent life.

Édouard Manet [edit]

Information technology is about impossible to ascribe Manet's piece of work to any one era or style of art. One of his works that is truly on the brink of a new style is Le Ballet Espagnol (1862).[i] The figures' contours coincide with their gestures as a way to suggest depth in relation to one another and in relation to the setting. Manet besides accentuates the lack of equilibrium in this work to project to the viewer that he or she is on the edge of a moment that is seconds away from passing. The blurred, hazy sense of color and shadow in this work similarly identify the viewer in a fleeting moment.

In 1863, Manet extended his study of movement on flat sail with Le déjeuner sur l'herbe. The low-cal, colour, and composition are the same, simply he adds a new structure to the background figures. The adult female angle in the background is non completely scaled as if she were far away from the figures in the foreground. The lack of spacing is Manet'south method of creating snapshot, near-invasive motion similar to his blurring of the foreground objects in Le Ballet Espagnol.

Edgar Degas [edit]

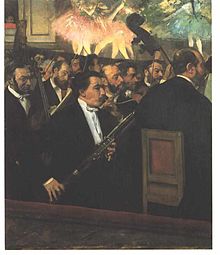

At the Races, 1877–1880, oil on canvas, by Edgar Degas, Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Edgar Degas is believed to be the intellectual extension of Manet, but more radical for the impressionist community. Degas' subjects are the paradigm of the impressionist era; he finds corking inspiration in images of ballet dancers and horse races. His "modern subjects"[7] never obscured his objective of creating moving art. In his 1860 piece Jeunes Spartiates south'exerçant à la lutte, he capitalizes on the classic impressionist nudes just expands on the overall concept. He places them in a flat landscape and gives them dramatic gestures, and for him this pointed to a new theme of "youth in movement".[8]

One of his well-nigh revolutionary works, Fifty'Orchestre de l'Opéra (1868) interprets forms of definite movement and gives them multidimensional movement across the flatness of the sheet. He positions the orchestra directly in the viewer'south space, while the dancers completely fill the groundwork. Degas is alluding to the Impressionist style of combining movement, but almost redefines information technology in a way that was seldom seen in the late 1800s. In the 1870s, Degas continues this trend through his dear of ane-shot motion horse races in such works as Voiture aux Courses (1872).

It wasn't until 1884 with Chevaux de Course that his attempt at creating dynamic art came to fruition. This work is role of a series of horse races and polo matches wherein the figures are well integrated into the landscape. The horses and their owners are depicted every bit if caught in a moment of intense deliberation, and and so trotting abroad casually in other frames. The impressionist and overall creative community were very impressed with this series, but were also shocked when they realized he based this series on bodily photographs. Degas was not fazed by the criticisms of his integration of photography, and it actually inspired Monet to rely on like engineering.

Claude Monet [edit]

Degas and Monet's mode was very similar in ane way: both of them based their artistic interpretation on a direct "retinal impression"[1] to create the feeling of variation and motility in their fine art. The subjects or images that were the foundation of their paintings came from an objective view of the globe. Equally with Degas, many art historians consider that to be the hidden effect photography had in that period of time. His 1860s works reflected many of the signs of movement that are visible in Degas' and Manet's piece of work.

By 1875, Monet'southward touch becomes very swift in his new series, get-go with Le Bâteau-Atelier sur la Seine. The landscape near engulfs the whole sail and has plenty movement emanating from its inexact brushstrokes that the figures are a part of the motion. This painting along with Gare Saint-Lazare (1877-1878), proves to many art historians that Monet was redefining the way of the Impressionist era. Impressionism initially was defined past isolating color, calorie-free, and movement.[7] In the late 1870s, Monet had pioneered a way that combined all 3, while maintaining a focus on the popular subjects of the Impressionist era. Artists were often so struck past Monet'south wispy brushstrokes that it was more than than movement in his paintings, but a hit vibration.[9]

Auguste Rodin [edit]

Auguste Rodin at commencement was very impressed by Monet'south 'vibrating works' and Degas' unique understanding of spatial relationships. Equally an artist and an author of art reviews, Rodin published multiple works supporting this style. He claimed that Monet and Degas' work created the illusion "that art captures life through good modeling and movement".[nine] In 1881, when Rodin first sculpted and produced his own works of fine art, he rejected his before notions. Sculpting put Rodin into a predicament that he felt no philosopher nor anyone could ever solve; how tin artists impart movement and dramatic motions from works so solid as sculptures? Afterwards this conundrum occurred to him, he published new articles that didn't attack men such as Manet, Monet, and Degas intentionally, merely propagated his own theories that Impressionism is not about communicating motion but presenting information technology in static form.

20th century surrealism and early kinetic art [edit]

The surrealist manner of the 20th century created an like shooting fish in a barrel transition into the style of kinetic art. All artists at present explored subject affair that would not have been socially acceptable to depict artistically. Artists went across solely painting landscapes or historical events, and felt the demand to delve into the mundane and the farthermost to interpret new styles.[10] With the support of artists such equally Albert Gleizes, other avant-garde artists such every bit Jackson Pollock and Max Pecker felt as if they had institute new inspiration to discover oddities that became the focus of kinetic art.

Albert Gleizes [edit]

Gleizes was considered the ideal philosopher of the late 19th century and early on 20th century arts in Europe, and more than specifically France. His theories and treatises from 1912 on cubism gave him a renowned reputation in any artistic give-and-take. This reputation is what allowed him to act with considerable influence when supporting the plastic fashion or the rhythmic movement of art in the 1910s and 1920s. Gleizes published a theory on movement, which farther articulated his theories on the psychological, artistic uses of movement in conjunction with the mentality that arises when considering movement. Gleizes asserted repeatedly in his publications that human creation implies the full renunciation of external sensation.[1] That to him is what made fine art mobile when to many, including Rodin, information technology was rigidly and unflinchingly immobile.

Gleizes first stressed the necessity for rhythm in art. To him, rhythm meant the visually pleasant coinciding of figures in a ii-dimensional or three-dimensional space. Figures should be spaced mathematically, or systematically so that they appeared to interact with one some other. Figures should likewise not take features that are too definite. They demand to have shapes and compositions that are well-nigh unclear, and from at that place the viewer can believe that the figures themselves are moving in that confined infinite. He wanted paintings, sculptures, and fifty-fifty the flat works of mid-19th-century artists to testify how figures could impart on the viewer that there was great movement contained in a certain space. Every bit a philosopher, Gleizes likewise studied the concept of artistic movement and how that appealed to the viewer. Gleizes updated his studies and publications through the 1930s, only equally kinetic art was becoming popular.

Jackson Pollock [edit]

When Jackson Pollock created many of his famous works, the United States was already at the forefront of the kinetic and popular art movements.[ citation needed ] The novel styles and methods he used to create his virtually famous pieces earned him the spot in the 1950s as the unchallenged leader of kinetic painters, his work was associated with Action painting coined by fine art critic Harold Rosenberg in the 1950s.[ citation needed ] Pollock had an unfettered desire to animate every attribute of his paintings.[ citation needed ] Pollock repeatedly said to himself, "I am in every painting".[eight] He used tools that most painters would never use, such equally sticks, trowels, and knives. He idea of the shapes he created equally being "beautiful, erratic objects".[8]

This style evolved into his drip technique. Pollock repeatedly took buckets of pigment and paintbrushes and flicked them around until the canvas was covered with squiggly lines and jagged strokes. In the next stage of his work, Pollock tested his style with uncommon materials. He painted his get-go piece of work with aluminum pigment in 1947, titled Cathedral and from there he tried his first "splashes" to destroy the unity of the material itself.[ citation needed ] He believed wholeheartedly that he was liberating the materials and structure of fine art from their forced confinements, and that is how he arrived at the moving or kinetic art that always existed.[ citation needed ]

Max Bill [edit]

Max Bill became an most complete disciple of the kinetic movement in the 1930s. He believed that kinetic fine art should exist executed from a purely mathematical perspective.[ commendation needed ] To him, using mathematics principles and understandings were one of the few ways that you could create objective motion.[ citation needed ] This theory applied to every artwork he created and how he created it. Bronze, marble, copper, and contumely were four of the materials he used in his sculptures.[ citation needed ] He besides enjoyed tricking the viewer's eye when he or she first approached one of his sculptures.[ commendation needed ] In his Construction with Suspended Cube (1935-1936) he created a mobile sculpture that generally appears to have perfect symmetry, only once the viewer glances at information technology from a unlike angle, there are aspects of asymmetry.[ commendation needed ]

Mobiles and sculpture [edit]

Max Bill's sculptures were but the beginning of the style of movement that kinetic explored. Tatlin, Rodchenko, and Calder especially took the stationary sculptures of the early 20th century and gave them the slightest freedom of movement. These iii artists began with testing unpredictable movement, and from there tried to control the motility of their figures with technological enhancements. The term "mobile" comes from the ability to modify how gravity and other atmospheric conditions affect the artist'south work.[7]

Although there is very petty distinction between the styles of mobiles in kinetic fine art, there is 1 distinction that tin can be made. Mobiles are no longer considered mobiles when the spectator has control over their movement. This is one of the features of virtual movement. When the piece only moves under certain circumstances that are not natural, or when the spectator controls the motion even slightly, the effigy operates nether virtual movement.[ citation needed ]

Kinetic fine art principles take also influenced mosaic art. For example, kinetic-influenced mosaic pieces often use clear distinctions between bright and dark tiles, with three-dimensional shape, to create apparent shadows and movement.[11]

Vladimir Tatlin [edit]

Russian creative person and founder-fellow member of the Russian Constructivism motility Vladimir Tatlin is considered past many artists and art historians[ who? ] to be the first person to ever complete a mobile sculpture.[ commendation needed ] The term mobile wasn't coined until Rodchenko's time,[ citation needed ] simply is very applicable to Tatlin's work. His mobile is a series of suspended reliefs that simply need a wall or a pedestal, and it would forever stay suspended. This early mobile, Contre-Reliefs Libérés Dans Fifty'espace (1915) is judged equally an incomplete work. It was a rhythm, much like to the rhythmic styles of Pollock, that relied on the mathematical interlocking of planes that created a work freely suspended in air.[ citation needed ]

Tatlin'due south Belfry or the project for the 'Monument to the Third International' (1919–20), was a design for a monumental kinetic architecture edifice that was never congenital.[12] It was planned to exist erected in Petrograd (at present Saint petersburg) after the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, as the headquarters and monument of the Comintern (the Third International).

Tatlin never felt that his art was an object or a product that needed a articulate outset or a clear end. He felt in a higher place anything that his work was an evolving process. Many artists whom he befriended considered the mobile truly consummate in 1936, but he disagreed vehemently.[ citation needed ]

Alexander Rodchenko [edit]

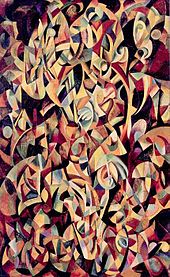

Alexander Rodchenko Trip the light fantastic toe. An Objectless Composition, 1915

Russian artist Alexander Rodchenko, Tatlin'due south friend and peer who insisted his work was complete, connected the study of suspended mobiles and created what he accounted to exist "non-objectivism".[1] This way was a written report less focused on mobiles than on canvas paintings and objects that were immovable. It focuses on juxtaposing objects of different materials and textures equally a way to spark new ideas in the mind of the viewer. By creating discontinuity with the piece of work, the viewer assumed that the figure was moving off the canvass or the medium to which it was restricted. One of his canvas works titled Dance, an Objectless Composition (1915) embodies that desire to place items and shapes of dissimilar textures and materials together to create an image that drew in the viewer'south focus.

However, by the 1920s and 1930s, Rodchenko found a style to contain his theories of non-objectivism in mobile study. His 1920 piece Hanging Structure is a wood mobile that hangs from any ceiling by a cord and rotates naturally. This mobile sculpture has concentric circles that exist in several planes, but the entire sculpture simply rotates horizontally and vertically.

Alexander Calder [edit]

Alexander Calder is an artist who many believe to have defined firmly and exactly the manner of mobiles in kinetic art. Over years of studying his works, many critics allege that Calder was influenced by a wide variety of sources. Some merits that Chinese windbells were objects that closely resembled the shape and top of his earliest mobiles. Other art historians fence that the 1920s mobiles of Man Ray, including Shade (1920) had a straight influence on the growth of Calder'due south art.

When Calder beginning heard of these claims, he immediately admonished his critics. "I have never been and never volition exist a product of anything more myself. My art is my own, why carp stating something nigh my art that isn't true?"[8] One of Calder'due south first mobiles, Mobile (1938) was the work that "proved" to many fine art historians that Man Ray had an obvious influence on Calder'southward fashion. Both Shade and Mobile have a single string fastened to a wall or a structure that keeps information technology in the air. The two works have a crinkled feature that vibrates when air passes through information technology.

Regardless of the obvious similarities, Calder'south style of mobiles created 2 types that are now referred to equally the standard in kinetic fine art. In that location are object-mobiles and suspended mobiles. Object mobiles on supports come in a wide range of shapes and sizes and can move in whatever style. Suspended mobiles were first made with colored drinking glass and pocket-sized wooden objects that hung on long threads. Object mobiles were a part of Calder'due south emerging fashion of mobiles that were originally stationary sculptures.

It tin be argued, based on their similar shape and stance, that Calder's earliest object mobiles have very picayune to practise with kinetic art or moving art. By the 1960s, well-nigh art critics believed that Calder had perfected the way of object mobiles in such creations as the Cat Mobile (1966).[thirteen] In this piece, Calder allows the cat'due south head and its tail to be subject field to random motion, but its body is stationary. Calder did non get-go the trend in suspended mobiles, but he was the creative person that became recognized for his apparent originality in mobile construction.

Ane of his primeval suspended mobiles, McCausland Mobile (1933),[fourteen] is different from many other contemporary mobiles just because of the shapes of the two objects. Most mobile artists such as Rodchenko and Tatlin would never have thought to use such shapes because they didn't seem malleable or fifty-fifty remotely aerodynamic.

Despite the fact that Calder did not divulge most of the methods he used when creating his work, he admitted that he used mathematical relationships to brand them. He simply said that he created a balanced mobile past using direct variation proportions of weight and distance. Calder's formulas changed with every new mobile he made, then other artists could never precisely imitate the piece of work.

Virtual movement [edit]

By the 1940s, new styles of mobiles, likewise as many types of sculpture and paintings, incorporated the command of the spectator. Artists such as Calder, Tatlin, and Rodchenko produced more art through the 1960s, but they were also competing confronting other artists who appealed to unlike audiences. When artists such every bit Victor Vasarely adult a number of the first features of virtual movement in their fine art, kinetic art faced heavy criticism. This criticism lingered for years until the 1960s, when kinetic art was in a dormant period.

Materials and electricity [edit]

Vasarely created many works that were considered to be interactive in the 1940s. I of his works Gordes/Cristal (1946) is a series of cubic figures that are besides electrically powered. When he first showed these figures at fairs and fine art exhibitions, he invited people upwardly to the cubic shapes to press the switch and start the colour and lite show. Virtual motility is a style of kinetic fine art that can be associated with mobiles, just from this manner of movement there are ii more specific distinctions of kinetic art.

Apparent motility and op art [edit]

Credible movement is a term ascribed to kinetic art that evolved simply in the 1950s. Art historians believed that any type of kinetic art that was mobile contained of the viewer has apparent movement. This style includes works that range from Pollock's baste technique all the mode to Tatlin's beginning mobile. By the 1960s, other art historians developed the phrase "op fine art" to refer to optical illusions and all optically stimulating art that was on sail or stationary. This phrase often clashes with sure aspects of kinetic art that include mobiles that are mostly stationary.[15] [16]

In 1955, for the exhibition Mouvements at the Denise René gallery in Paris, Victor Vasarely and Pontus Hulten promoted in their "Yellow manifesto" some new kinetic expressions based on optical and luminous phenomenon as well as painting illusionism. The expression "kinetic fine art" in this modern class start appeared at the Museum für Gestaltung of Zürich in 1960, and establish its major developments in the 1960s. In nearly European countries, it generally included the class of optical fine art that mainly makes use of optical illusions, such as op art, represented by Bridget Riley, likewise every bit art based on movement represented by Yacov Agam, Carlos Cruz-Diez, Jesús Rafael Soto, Gregorio Vardanega, Martha Boto or Nicolas Schöffer. From 1961 to 1968, GRAV (Groupe de Recherche d'Fine art Visuel) founded by François Morellet, Julio Le Parc, Francisco Sobrino, Horacio Garcia Rossi, Yvaral, Joël Stein and Vera Molnár was a collective group of opto-kinetic artists. According to its 1963 manifesto, GRAV appealed to the direct participation of the public with an influence on its beliefs, notably through the use of interactive labyrinths.

Contemporary work [edit]

In Nov 2013, the MIT Museum opened 5000 Moving Parts, an exhibition of kinetic fine art, featuring the work of Arthur Ganson, Anne Lilly, Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, John Douglas Powers, and Takis. The exhibition inaugurates a "year of kinetic art" at the Museum, featuring special programming related to the artform.[17]

Neo-kinetic[ clarification needed ] art has been pop in Communist china where y'all can find interactive kinetic sculptures in many public places, including Wuhu International Sculpture Park and in Beijing.[18]

Changi Airport, Singapore has a curated collection of artworks including big-scale kinetic installations by international artists Art+COM and Christian Moeller.[ citation needed ]

Selected works [edit]

-

-

-

-

-

-

Uli Aschenborn, if the onlooker passes this 'chameleon-painting' Magic Die it shows i, 2 or 3 pips and its colour changes - sand and paint, Namibia

-

Sarnikoff 'Goldflakes' Mobile cardboard animated by an asynchronous motor, besides recycle art to bring spirit in this contribution France

-

Selected kinetic sculptors [edit]

- Yaacov Agam

- Uli Aschenborn

- David Ascalon

- Fletcher Benton

- Mark Bischof

- Daniel Buren

- Alexander Calder

- Gregorio Vardanega

- Martha Boto

- U-Ram Choe

- Angela Conner

- Carlos Cruz-Diez

- Marcel Duchamp

- Lin Emery

- Rowland Emett

- Arthur Ganson

- Nemo Gould

- Gerhard von Graevenitz

- Bruce Gray

- Ralfonso Gschwend

- Rafael Lozano-Hemmer

- Chuck Hoberman

- Anthony Howe

- Irma Hünerfauth

- Tim Hunkin

- Theo Jansen

- Ned Kahn

- Roger Katan

- Starr Kempf

- Frederick Kiesler

- Viacheslav Koleichuk

- Gyula Kosice

- Gilles Larrain

- Julio Le Parc

- Liliane Lijn

- Len Lye

- Sal Maccarone

- Heinz Mack

- Phyllis Marker

- László Moholy-Nagy

- Alejandro Otero

- Robert Perless

- Otto Piene

- George Rickey

- Ken Rinaldo

- Barton Rubenstein

- Nicolas Schöffer

- Eusebio Sempere

- Jesús Rafael Soto

- Marker di Suvero

- Takis

- Jean Tinguely

- Wen-Ying Tsai

- Marc van den Broek

- Panayiotis Vassilakis

- Lyman Whitaker

- Ludwig Wilding

Selected kinetic op artists [edit]

- Nadir Afonso

- Getulio Alviani

- Marina Apollonio

- Carlos Cruz-Díez

- Ronald Mallory

- Youri Messen-Jaschin

- Vera Molnár

- Abraham Palatnik

- Bridget Riley

- Eusebio Sempere

- Grazia Varisco

- Victor Vasarely

- Jean-Pierre Yvaral

- Romano Rizzato

See also [edit]

- Bulwark-grid animation § Kinegram

- Gas sculpture

- Lumino kinetic art

- Robotic art

- Sound art

- Audio installation

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d e Popper, Frank (1968). Origins and Development of Kinetic Art. New York Graphic Gild.

- ^ Lijn, Liliane (2018-06-eleven). "Accepting the Machine: A Response by Liliane Lijn to Three Questions from Arts". Arts. vii (two): 21. doi:10.3390/arts7020021.

- ^ Popper, Frank (2003), "Kinetic fine art", Oxford Fine art Online, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t046632

- ^ a b Leaper, Laura E. (2010-02-24), "Kinetic art in America", Oxford Art Online, Oxford Academy Press, doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t2085921

- ^ Popper, Frank. Kinetics.

- ^ Brett, Guy (1968). Kinetic fine art. London, New York: Studio-Vista. ISBN978-0-289-36969-2. OCLC 439251.

- ^ a b c Kepes, Gyorgy (1965). The Nature and Fine art of Motion. Grand. Braziller.

- ^ a b c d Malina, Frank J. Kinetic Art: Theory and Practice .

- ^ a b Roukes, Nicholas (1974). Plastics for Kinetic Art. Watson-Guptill Publications. ISBN978-0-8230-4029-2.

- ^ Giedion-Welcker, Carola (1937). Mod Plastic Art, Elements of Reality, Book and Disintegration. H. Girsberger.

- ^ Menhem, Chantal. "Kinetic Mosaics: The Fine art of Movement". Mozaico . Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- ^ Janson, H.W. (1995). History of Art. fifth ed., Revised and expanded by Anthony F. Janson. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 820. ISBN0500237018.

- ^ Mulas, Ugo; Arnason, H. Harvard. Calder . with comments by Alexander Calder.

- ^ Marter, Joan M. (1997). Alexander Calder. Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-0-521-58717-iv.

- ^ "Op fine art". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ "Fine art cinétique". Site Internet du Centre Pompidou (in French).

- ^ "5000 Moving Parts". MIT Museum. MIT Museum. Retrieved 2013-11-29 .

- ^ Gschwend, Ralfonso (22 July 2015). "The Development of Public Art and its Time to come Passive, Active and Interactive Past, Present and Future". Arts. four (3): 93–100. doi:10.3390/arts4030093.

Further reading [edit]

- Terraroli, Valerio (2008). The Birth of Gimmicky Fine art: 1946-1968 . Rizzoli Publishing. ISBN9788861301948.

- Tovey, John (1971). The Technique of Kinetic Art. David and Charles. ISBN9780713425185.

- Selz, Peter Howard (1984). Theories of Modern Art: A Source Book by Artists and Critics . University of California Press. ISBN9780520052567.

- Selz, Peter; Chattopadhyay, Collette; Ghirado, Diane (2009). Fletcher Benton: The Kinetic Years. Hudson Hills Press. ISBN9781555952952.

- Marks, Mickey K. (1972). Op-Tricks: Creating Kinetic Art . Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN9780397312177.

- Diehl, Gaston (1991). Vasarely. Crown Publishing Group. ISBN9780517508008.

- Milner, John (2009). Rodchenko: Blueprint. Antiquarian Collector's Club. ISBN9781851495917.

- Bott Casper, Gian (2012). Tatlin: Art for a New Globe. Hatje Cantz Verlag GmbH & Co KG. ISBN9783775733632.

- Toynton, Evelyn (2012). Jackson Pollock . Yale University Printing. ISBN9780300192506.

External links [edit]

- Kinetic Art Organization (KAO) - KAO - Largest International Kinetic Art Organisation (Kinetic Fine art film and book library, KAO Museum planned)

mcclemenshisherear97.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kinetic_art

0 Response to "3 Main Types of Motion and Kinematic Arts Movies"

Post a Comment