Unit 3 Reading Guide Byzantine Empire, Islam, and Africa

| Arab–Byzantine wars | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Function of the Muslim conquests | |||||||

| Greek burn down, commencement used by the Byzantine Navy during the Arab–Byzantine Wars. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Byzantine Empire[annotation 1] Ghassanids[1] Mardaites Armenian principalities Bulgarian Empire Kingdom of Italia Italian metropolis-states | Medina Islamic Government Rashidun Caliphate Umayyad Caliphate Abbasid Caliphate Aghlabid Emirate of Abbasids Emirate of Bari Emirate of Crete Hamdanids of Aleppo Mirdasids of Aleppo | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Heraclius Theodore Trithyrius † Gregory the Patrician † Vahan † Niketas the Persian † Constans 2 Constantine IV Justinian II Leontios Heraclius Constantine V Leo V the Armenian Michael Lachanodrakon Tatzates Irene of Athens Nikephoros I † Theophilos Manuel the Armenian Niketas Ooryphas Himerios John Kourkouas Bardas Phokas the Elderberry Nikephoros II Phokas Leo Phokas the Younger John I Tzimiskes Michael Bourtzes Basil Two Nikephoros Ouranos George Maniakes Tervel of Bulgaria | Muhammad Al-Aziz Billah Manjutakin | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 8,000 in Bosra[2] 50,000 at Yarmouk[3] ~7,000 at Hazir[4] 10,000+ at Iron Bridge[five] | 300 at Dathin[6] 130 in Bosra[2] 3000 in Yarmouk[three] ~l,000 at Constantinople[vii] ~2500 ships at Constantinople[8] | ||||||

| four,000 civilian deaths at Dathin[9] | |||||||

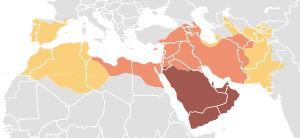

The Arab–Byzantine wars were a series of wars between a number of Muslim Arab dynasties and the Byzantine Empire between the 7th and 12th centuries Ad. Conflict started during the initial Muslim conquests, nether the expansionist Rashidun and Umayyad caliphs, in the 7th century and connected by their successors until the mid-12th century.

The emergence of Muslim Arabs from Arabia in the 630s resulted in the rapid loss of Byzantium'south southern provinces (Syria and Egypt) to the Arab Caliphate. Over the next fifty years, under the Umayyad caliphs, the Arabs would launch repeated raids into nonetheless-Byzantine Asia Pocket-size, twice congregate the Byzantine capital of Constantinople, and conquer the Byzantine Exarchate of Africa. The situation did not stabilize until afterwards the failure of the Second Arab Siege of Constantinople in 718, when the Taurus Mountains on the eastern rim of Asia Modest became established equally the mutual, heavily fortified and largely depopulated frontier. Under the Abbasid Empire, relations became more than normal, with embassies exchanged and fifty-fifty periods of truce, but disharmonize remained the norm, with almost annual raids and counter-raids, sponsored either by the Abbasid government or by local rulers, well into the 10th century.

During the first centuries, the Byzantines were usually on the defensive, and avoided open field battles, preferring to retreat to their fortified strongholds. Only after 740 did they brainstorm to launch their raids in an try to gainsay the Arabs and take the lands they had lost, only still the Abbasid Empire was able to retaliate with often massive and destructive invasions of Asia Minor. With the decline and fragmentation of the Abbasid state after 861 and the concurrent strengthening of the Byzantine Empire under the Macedonian dynasty, the tide gradually turned. Over a catamenia of fifty years from ca. 920 to 976, the Byzantines finally bankrupt through the Muslim defences and restored their control over northern Syria and Greater Armenia. The last century of the Arab–Byzantine wars was dominated by frontier conflicts with the Fatimids in Syria, only the edge remained stable until the advent of a new people, the Seljuk Turks, after 1060.

The Arabs also took to the sea, and from the 650s on, the unabridged Mediterranean Sea became a battleground, with raids and counter-raids existence launched against islands and the coastal settlements. Arab raids reached a peak in the 9th and early 10th centuries, after the conquests of Crete, Malta and Sicily, with their fleets reaching the coasts of France and Dalmatia and even the suburbs of Constantinople.

Groundwork [edit]

The prolonged and escalating Byzantine–Sasanian wars of the 6th and 7th centuries and the recurring outbreaks of bubonic plague (Plague of Justinian) left both empires wearied and vulnerable in the face of the sudden emergence and expansion of the Arabs. The final of the wars betwixt the Roman and Farsi empires ended with victory for the Byzantines: Emperor Heraclius regained all lost territories, and restored the True Cantankerous to Jerusalem in 629.[10]

Even so, neither empire was given whatsoever adventure to recover, as within a few years they plant themselves in conflict with the Arabs (newly united by Islam), which, according to Howard-Johnston, "tin only be likened to a man tsunami".[11] According to George Liska, the "unnecessarily prolonged Byzantine–Farsi conflict opened the way for Islam".[12]

In the late 620s, the Islamic Prophet Muhammad had already managed to unify much of Arabia under Muslim rule via conquest as well as making alliances with neighboring tribes, and information technology was under his leadership that the first Muslim–Byzantine skirmishes took place. Just a few months after Emperor Heraclius and the Western farsi general Shahrbaraz agreed on terms for the withdrawal of Persian troops from occupied Byzantine eastern provinces in 629, Arab and Byzantine troops confronted each other at the battle of Mu'tah. [thirteen] Muhammad died in 632 and was succeeded by Abu Bakr, the first Caliph with undisputed command of the entire Arabian Peninsula later the successful Ridda wars, which resulted in the consolidation of a powerful Muslim state throughout the peninsula.[fourteen]

Muslim conquests, 629–718 [edit]

According to Muslim biographies, Muhammed, having received intelligence that Byzantine forces were concentrating in northern Arabia with intentions of invading Arabia, led a Muslim army north to Tabuk in nowadays-day northwestern Saudi arabia, with the intention of pre-emptively engaging the Byzantine ground forces, nevertheless, the Byzantine army had retreated beforehand. Though it was not a battle in the typical sense, notwithstanding the effect represented the starting time Arab run across against the Byzantines. Information technology did not, nevertheless, lead immediately to a military confrontation.[15]

There is no gimmicky Byzantine account of the Tabuk trek, and many of the details come from much later Muslim sources. Information technology has been argued that in that location is in one Byzantine source perhaps referencing the Boxing of Mu´tah traditionally dated 629, but this is non certain.[16] The outset engagements may have started as conflicts with the Arab client states of the Byzantine and Sassanid empires: the Ghassanids and the Lakhmids of Al-Hirah. In any example, Muslim Arabs after 634 certainly pursued a full-blown offensive against both empires, resulting in the conquest of the Levant, Egypt and Persia for Islam. The most successful Arab generals were Khalid ibn al-Walid and 'Amr ibn al-'As.

Arab conquest of Roman Syria: 634–638 [edit]

In the Levant, the invading Rashidun army were engaged past a Byzantine regular army composed of majestic troops besides as local levies.[note 1] According to Islamic historians, Monophysites and Jews throughout Syria welcomed the Arabs equally liberators, as they were discontented with the rule of the Byzantines.[annotation 2]

The Roman Emperor Heraclius had fallen ill and was unable to personally lead his armies to resist the Arab conquests of Syria and Roman Paelestina in 634. In a battle fought near Ajnadayn in the summer of 634, the Rashidun Caliphate army achieved a decisive victory.[eighteen] After their victory at the Fahl, Muslim forces conquered Damascus in 634 under the command of Khalid ibn al-Walid.[19] The Byzantine response involved the collection and acceleration of the maximum number of available troops nether major commanders, including Theodore Trithyrius and the Armenian general Vahan, to eject the Muslims from their newly won territories.[19]

At the Battle of Yarmouk in 636, however, the Muslims, having studied the ground in detail, lured the Byzantines into pitched battle, which the Byzantines normally avoided, and into a series of costly assaults, before turning the deep valleys and cliffs into a catastrophic death-trap.[20] Heraclius' bye exclamation (according to the 9th-century historian Al-Baladhuri)[21] while departing Antioch for Constantinople, is expressive of his disappointment: "Peace unto thee, O Syrian arab republic, and what an first-class land this is for the enemy!"[note 3] The affect of Syria's loss on the Byzantines is illustrated by Joannes Zonaras' words: "[...] since then [after the fall of Syria] the race of the Ishmaelites did not cease from invading and plundering the entire territory of the Romans".[24]

In April 637 the Arabs, after a long siege, captured Jerusalem, which was surrendered by Patriarch Sophronius.[note 4] In the summer of 637, the Muslims conquered Gaza, and, during the same period, the Byzantine authorities in Arab republic of egypt and Mesopotamia purchased an expensive truce, which lasted three years for Egypt and 1 year for Mesopotamia. Antioch cruel to the Muslim armies in belatedly 637, and by and then the Muslims occupied the whole of northern Syrian arab republic, except for upper Mesopotamia, which they granted a one-year truce.[16]

At the expiration of this truce in 638–639, the Arabs overran Byzantine Mesopotamia and Byzantine Armenia, and terminated the conquest of Palestine by storming Caesarea Maritima and effecting their terminal capture of Ascalon. In December 639, the Muslims departed from Palestine to invade Arab republic of egypt in early 640.[16]

Arab conquests of North Africa: 639–698 [edit]

Conquest of Egypt and Cyrenaica [edit]

Past the fourth dimension Heraclius died, much of Egypt had been lost, and past 637–638 the whole of Syria was in the easily of the armies of Islam.[notation 5] With 3,500–four,000 troops under his command, 'Amr ibn al-A'as first crossed into Egypt from Palestine at the finish of 639 or the beginning of 640. He was progressively joined by farther reinforcements, notably 12,000 soldiers by Zubayr ibn al-Awwam. 'Amr first besieged and conquered Babylon, and then attacked Alexandria. The Byzantines, divided and shocked by the sudden loss of so much territory, agreed to give up the metropolis by September 642.[27] The fall of Alexandria extinguished Byzantine dominion in Egypt, and immune the Muslims to continue their military expansion into N Africa; between 643 and 644 'Amr completed the conquest of Cyrenaica.[28] Uthman succeeded Caliph Umar after his death.[29]

Co-ordinate to Arab historians, the local Christian Copts welcomed the Arabs but as the Monophysites did in Jerusalem.[30] The loss of this lucrative province deprived the Byzantines of their valuable wheat supply, thereby causing food shortages throughout the Byzantine Empire and weakening its armies in the post-obit decades.[31]

The Byzantine navy briefly won back Alexandria in 645, but lost it again in 646 shortly later on the Battle of Nikiou.[32] The Islamic forces raided Sicily in 652, while Cyprus and Crete were captured in 653.

Conquest of the Exarchate of Africa [edit]

| "The people of Homs replied [to the Muslims], "Nosotros like your rule and justice far better than the state of oppression and tyranny in which we were. The army of Heraclius nosotros shall indeed, with your 'amil'due south' help, repulse from the urban center." The Jews rose and said, "We swear by the Torah, no governor of Heraclius shall enter the city of Homs unless we are beginning vanquished and exhausted!" [...] The inhabitants of the other cities—Christian and Jews—that had capitulated to the Muslims, did the same [...] When by Allah's help the "unbelievers" were defeated and the Muslims won, they opened the gates of their cities, went out with the singers and music players who began to play, and paid the kharaj." |

| Al-Baladhuri[33] – According to the Muslim historians of the 9th century, local populations regarded Byzantine rule every bit oppressive, and preferred Muslim conquest instead.[a] |

In 647, a Rashidun-Arab ground forces led past Abdallah ibn al-Sa'ad invaded the Byzantine Exarchate of Africa. Tripolitania was conquered, followed past Sufetula, 150 miles (240 km) due south of Carthage, and the governor and cocky-proclaimed Emperor of Africa Gregory was killed. Abdallah'southward booty-laden force returned to Egypt in 648 after Gregory'south successor, Gennadius, promised them an annual tribute of some 300,000 nomismata.[34]

Post-obit a civil war in the Arab Empire the Umayyads came to power under Muawiyah I. Nether the Umayyads the conquest of the remaining Byzantine and northern Berber territories in North Africa was completed and the Arabs were able to move across large parts of the Berber world, invading Visigothic Spain through the Strait of Gibraltar,[30] under the command of the allegedly Berber full general Tariq ibn-Ziyad. But this happened only later they adult a naval power of their own,[note 6] and they conquered and destroyed the Byzantine stronghold of Carthage between 695 and 698.[36] The loss of Africa meant that soon, Byzantine control of the Western Mediterranean was challenged by a new and expanding Arab fleet, operating from Tunisia.[37]

Muawiyah began consolidating the Arab territory from the Aral Sea to the western border of Egypt. He put a governor in identify in Egypt at al-Fustat, and launched raids into Anatolia in 663. Then from 665 to 689 a new Northward African campaign was launched to protect Egypt "from flank assault by Byzantine Cyrene". An Arab army of 40,000 took Barca, defeating thirty,000 Byzantines.[38]

A vanguard of ten,000 Arabs under Uqba ibn Nafi followed from Damascus. In 670, Kairouan in modernistic Tunisia was established as a base for farther invasions; Kairouan would become the capital letter of the Islamic province of Ifriqiya, and i of the main Arabo-Islamic religious centers in the Middle Ages.[39] Then ibn Nafi "plunged into the center of the country, traversed the wilderness in which his successors erected the first-class capitals of Fes and Kingdom of morocco, and at length penetrated to the verge of the Atlantic and the great desert".[forty]

In his conquest of the Maghreb, Uqba Ibn Nafi took the littoral cities of Bejaia and Tangier, overwhelming what had once been the Roman province of Mauretania where he was finally halted.[41] As the historian Luis Garcia de Valdeavellano explains:[42]

In their struggle confronting the Byzantines and the Berbers, the Arab chieftains had profoundly extended their African dominions, and as early as the year 682 Uqba had reached the shores of the Atlantic, but he was unable to occupy Tangier, for he was forced to turn back toward the Atlas Mountains by a human who became known to history and legend as Count Julian.

—Luis Garcia de Valdeavellano

Arab attacks on Anatolia and sieges of Constantinople [edit]

Every bit the first tide of the Muslim conquests in the Near Eastward ebbed off, and a semi-permanent border between the two powers was established, a wide zone, unclaimed by either Byzantines or Arabs and nigh deserted (known in Arabic as al-Ḍawāḥī, "the outer lands" and in Greek equally τὰ ἄκρα , ta akra, "the extremities") emerged in Cilicia, along the southern approaches of the Taurus and Anti-Taurus mountain ranges, leaving Syrian arab republic in Muslim and the Anatolian plateau in Byzantine easily. Both Emperor Heraclius and the Caliph 'Umar (r. 634–644) pursued a strategy of destruction inside this zone, trying to transform it into an effective bulwark betwixt the two realms.[43]

However, the Umayyads still considered the consummate subjugation of Byzantium as their ultimate objective. Their thinking was dominated by Islamic teaching, which placed the infidel Byzantines in the Dār al-Ḥarb, the "House of War", which, in the words of Islamic scholar Hugh N. Kennedy, "the Muslims should attack whenever possible; rather than peace interrupted by occasional conflict, the normal design was seen to be conflict interrupted past occasional, temporary truce (hudna). True peace (ṣulḥ) could but come when the enemy accepted Islam or tributary status."[44]

Both as governor of Syria and later on as caliph, Muawiyah I (r. 661–680) was the driving force of the Muslim attempt confronting Byzantium, especially past his creation of a fleet, which challenged the Byzantine navy and raided the Byzantine islands and coasts. To stop the Byzantine harassment from the sea during the Arab-Byzantine Wars, in 649 Muawiyah prepare a navy, manned past Monophysitise Christian, Copt and Jacobite Syrian Christian sailors and Muslim troops. This resulted in the defeat of the Byzantine navy at the Battle of the Masts in 655, opening up the Mediterranean.[45] [46] [47] [48] [49] The shocking defeat of the imperial armada by the young Muslim navy at the Boxing of the Masts in 655 was of disquisitional importance: it opened up the Mediterranean, hitherto a "Roman lake", to Arab expansion, and began a centuries-long series of naval conflicts over the control of the Mediterranean waterways.[fifty] [51] 500 Byzantine ships were destroyed in the boxing, and Emperor Constans Ii was almost killed. Under the instructions of the caliph Uthman ibn Affan, Muawiyah then prepared for the siege of Constantinople.

Trade between the Muslim eastern and southern shores and the Christian northern shores most ceased during this period, isolating Western Europe from developments in the Muslim world: "In antiquity, and again in the high Middle Ages, the voyage from Italy to Alexandria was commonplace; in early on Islamic times the two countries were and so remote that even the most basic information was unknown" (Kennedy).[52] Muawiyah likewise initiated the first large-scale raids into Anatolia from 641 on. These expeditions, aiming both at plunder and at weakening and keeping the Byzantines at bay, equally well as the corresponding retaliatory Byzantine raids, eventually became established as a fixture of Byzantine–Arab warfare for the adjacent three centuries.[53] [54]

The outbreak of the Muslim Ceremonious War in 656 bought a precious breathing pause for Byzantium, which Emperor Constans II (r. 641–668) used to shore up his defences, extend and consolidate his command over Armenia and most importantly, initiate a major army reform with lasting outcome: the establishment of the themata, the large territorial commands into which Anatolia, the major contiguous territory remaining to the Empire, was divided. The remains of the old field armies were settled in each of them, and soldiers were allocated land there in payment of their service. The themata would form the backbone of the Byzantine defensive system for centuries to come.[55]

Attacks against Byzantine holdings in Africa, Sicily and the East [edit]

Afterward his victory in the ceremonious war, Muawiyah launched a series of attacks confronting Byzantine holdings in Africa, Sicily and the East.[56] Past 670, the Muslim armada had penetrated into the Bounding main of Marmara and stayed at Cyzicus during the wintertime. Four years later on, a massive Muslim fleet reappeared in the Marmara and re-established a base at Cyzicus, from at that place they raided the Byzantine coasts almost at will. Finally in 676, Muawiyah sent an army to invest Constantinople from land as well, beginning the Kickoff Arab Siege of the city. Constantine IV (r. 661–685) withal used a devastating new weapon that came to exist known as "Greek burn down", invented past a Christian refugee from Syria named Kallinikos of Heliopolis, to decisively defeat the attacking Umayyad navy in the Bounding main of Marmara, resulting in the lifting of the siege in 678. The returning Muslim fleet suffered farther losses due to storms, while the army lost many men to the thematic armies who attacked them on their route back.[57]

Among those killed in the siege was Eyup, the standard bearer of Muhammed and the terminal of his companions; to Muslims today, his tomb is considered i of the holiest sites in Istanbul.[58] The Byzantine victory over the invading Umayyads halted the Islamic expansion into Europe for almost 30 years.[ citation needed ]

In spite of the turbulent reign of Justinian 2, last emperor of the Heraclian dynasty, his coinage still bore the traditional "PAX", peace.

The setback at Constantinople was followed by further reverses beyond the vast Muslim empire. As Gibbon writes, "this Mahometan Alexander, who sighed for new worlds, was unable to preserve his recent conquests. By the universal defection of the Greeks and Africans he was recalled from the shores of the Atlantic." His forces were directed at putting down rebellions, and in 1 such battle he was surrounded by insurgents and killed. Then, the third governor of Africa, Zuheir, was overthrown by a powerful regular army, sent from Constantinople by Constantine IV for the relief of Carthage.[41] Meanwhile, a second Arab ceremonious war was raging in Arabia and Syrian arab republic resulting in a series of 4 caliphs between the death of Muawiyah in 680 and the ascension of Abd al-Malik in 685, and was ongoing until 692 with the death of the rebel leader.[59]

The Saracen Wars of Justinian 2 (r. 685–695 and 705–711), last emperor of the Heraclian Dynasty, "reflected the general anarchy of the age".[lx] After a successful campaign he fabricated a truce with the Arabs, agreeing on articulation possession of Armenia, Iberia and Republic of cyprus; withal, by removing 12,000 Christian Mardaites from their native Lebanon, he removed a major obstacle for the Arabs in Syrian arab republic, and in 692, after the disastrous Battle of Sebastopolis, the Muslims invaded and conquered all of Armenia.[61] Deposed in 695, with Carthage lost in 698, Justinian returned to ability from 705 to 711.[60] His second reign was marked by Arab victories in Asia Minor and civil unrest.[61] Reportedly, he ordered his guards to execute the only unit that had non deserted him afterwards 1 battle, to foreclose their desertion in the next.[60]

Justinian's first and second depositions were followed by internal disorder, with successive revolts and emperors lacking legitimacy or back up. In this climate, the Umayyads consolidated their control of Armenia and Cilicia, and began preparing a renewed offensive against Constantinople. In Byzantium, the general Leo the Isaurian (r. 717–741) had just seized the throne in March 717, when the massive Muslim army under the famed Umayyad prince and general Maslama ibn Abd al-Malik began moving towards the imperial majuscule.[62] The Caliphate's army and navy, led by Maslama, numbered some 120,000 men and 1,800 ships according to the sources. Whatever the real number, it was a huge force, far larger than the regal regular army. Thankfully for Leo and the Empire, the capital's ocean walls had recently been repaired and strengthened. In add-on, the emperor concluded an brotherhood with the Bulgar khan Tervel, who agreed to harass the invaders' rear.[8]

From July 717 to August 718, the city was besieged by land and body of water past the Muslims, who built an extensive double line of circumvallation and contravallation on the landward side, isolating the capital. Their attempt to complete the occludent past bounding main however failed when the Byzantine navy employed Greek fire against them; the Arab fleet kept well off the city walls, leaving Constantinople's supply routes open. Forced to extend the siege into winter, the besieging ground forces suffered horrendous casualties from the cold and the lack of provisions.[63]

In bound, new reinforcements were sent by the new caliph, Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz (r. 717–720), by body of water from Africa and Egypt and over land through Asia Minor. The crews of the new fleets were composed mostly of Christians, who began defecting in big numbers, while the land forces were ambushed and defeated in Bithynia. Every bit famine and an epidemic connected to plague the Arab campsite, the siege was abandoned on 15 August 718. On its return, the Arab fleet suffered further casualties to storms and an eruption of the volcano of Thera.[64]

Stabilization of the frontier, 718–863 [edit]

The first wave of the Muslim conquests ended with the siege of Constantinople in 718, and the border betwixt the two empires became stabilized along the mountains of eastern Anatolia. Raids and counter-raids continued on both sides and became most ritualized, but the prospect of outright conquest of Byzantium past the Caliphate receded. This led to far more regular, and oftentimes friendly, diplomatic contacts, equally well as a reciprocal recognition of the 2 empires.

In response to the Muslim threat, which reached its top in the offset half of the 8th century, the Isaurian emperors adopted the policy of Iconoclasm, which was abased in 786 only to be readopted in the 820s and finally abased in 843. Under the Macedonian dynasty, exploiting the turn down and fragmentation of the Abbasid Caliphate, the Byzantines gradually went on the offensive, and recovered much territory in the tenth century, which was lost however after 1071 to the Seljuk Turks.

Raids nether the concluding Umayyads and the rising of Iconoclasm [edit]

Map of the Byzantine-Arab frontier zone in southeastern Asia Small, along the Taurus-Antitaurus range

Following the failure to capture Constantinople in 717–718, the Umayyads for a time diverted their attending elsewhere, assuasive the Byzantines to have to the offensive, making some gains in Armenia. From 720/721 yet the Arab armies resumed their expeditions confronting Byzantine Anatolia, although now they were no longer aimed at conquest, but rather large-scale raids, plundering and devastating the countryside and merely occasionally attacking forts or major settlements.[65] [66]

Under the tardily Umayyad and early Abbasid caliphs, the frontier betwixt Byzantium and the Caliphate became stabilized along the line of the Taurus-Antitaurus mountain ranges. On the Arab side, Cilicia was permanently occupied and its deserted cities, such equally Adana, Mopsuestia (al-Massisa) and, about chiefly, Tarsus, were refortified and resettled under the early on Abbasids. As well, in Upper Mesopotamia, places similar Germanikeia (Mar'ash), Hadath and Melitene (Malatya) became major military machine centers. These two regions came to grade the two-halves of a new fortified frontier zone, the thughur.[54] [67]

Both the Umayyads and later the Abbasids connected to regard the almanac expeditions against the Caliphate's "traditional enemy" as an integral part of the continuing jihad, and they quickly became organized in a regular manner: one to two summer expeditions (pl. ṣawā'if, sing. ṣā'ifa) sometimes accompanied by a naval assault and/or followed past winter expeditions (shawātī). The summer expeditions were usually ii split attacks, the "expedition of the left" (al-ṣā'ifa al-yusrā/al-ṣughrā) launched from the Cilician thughur and consisting by and large of Syrian troops, and the usually larger "expedition of the right" (al-ṣā'ifa al-yumnā/al-kubrā) launched from Malatya and composed of Mesopotamian troops. The raids were also largely bars to the borderlands and the central Anatolian plateau, and only rarely reached the peripheral coastlands, which the Byzantines fortified heavily.[65] [68]

Under the more ambitious Caliph Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik (r. 723–743), the Arab expeditions intensified for a time, and were led by some of the Caliphate'southward most capable generals, including princes of the Umayyad dynasty like Maslama ibn Abd al-Malik and al-Abbas ibn al-Walid or Hisham'due south own sons Mu'awiyah, Maslama and Sulayman.[69] This was even so a time when Byzantium was fighting for survival, and "the frontier provinces, devastated by war, were a land of ruined cities and deserted villages where a scattered population looked to rocky castles or impenetrable mountains rather than the armies of the empire to provide a minimum of security" (Kennedy).[44]

In response to the renewal of Arab invasions, and to a sequence of natural disasters such every bit the eruptions of the volcanic island of Thera,[seventy] the Emperor Leo III the Isaurian concluded that the Empire had lost divine favour. Already in 722 he had tried to force the conversion of the Empire'southward Jews, just shortly he began to turn his attention to the veneration of icons, which some bishops had come up to regard as idolatrous. In 726, Leo published an edict condemning their use and showed himself increasingly critical of the iconophiles. He formally banned depictions of religious figures in a court council in 730.[71] [72]

This decision provoked major opposition both from the people and the church building, specially the bishop of Rome, which Leo did not have into business relationship. In the words of Warren Treadgold: "He saw no need to consult the church, and he appears to accept been surprised by the depth of the pop opposition he encountered".[71] [72] The controversy weakened the Byzantine Empire, and was a key cistron in the schism between the patriarch of Constantinople and the bishop of Rome.[73] [74]

The Umayyad Caliphate however was increasingly distracted past conflicts elsewhere, specially its confrontation with the Khazars, with whom Leo III had concluded an alliance, marrying his son and heir, Constantine V (r. 741–775) to the Khazar princess Tzitzak. Only in the late 730s did the Muslim raids once again become a threat, only the great Byzantine victory at Akroinon and the turmoil of the Abbasid Revolution led to a pause in Arab attacks confronting the Empire. It also opened upwards the fashion for a more than ambitious stance by Constantine 5 (r. 741–775), who in 741 attacked the major Arab base of Melitene, and continued scoring further victories. These successes were also interpreted by Leo 3 and his son Constantine as evidence of God's renewed favour, and strengthened the position of Iconoclasm within the Empire.[75] [76]

Early on Abbasids [edit]

Unlike their Umayyad predecessors, the Abbasid caliphs did non pursue active expansion: in general terms, they were content with the territorial limits achieved, and whatever external campaigns they waged were retaliatory or preemptive, meant to preserve their frontier and impress Abbasid might upon their neighbours.[77] At the same time, the campaigns against Byzantium in particular remained of import for domestic consumption. The annual raids, which had nigh lapsed in the turmoil post-obit the Abbasid Revolution, were undertaken with renewed vigour from ca. 780 on, and were the only expeditions where the Caliph or his sons participated in person.[78] [79]

As a symbol of the Caliph's ritual function every bit the leader of the Muslim community, they were closely paralleled in official propaganda past the leadership by Abbasid family members of the annual pilgrimage (hajj) to Mecca.[78] [79] In addition, the constant warfare on the Syrian marches was useful to the Abbasids as information technology provided employment for the Syrian and Iraqi armed forces elites and the various volunteers (muṭṭawi'a) who flocked to participate in the jihad.[80] [81]

"The thughūr are blocked past Hārūn, and through him

the ropes of the Muslim country are firmly plaited

His banner is forever tied with victory;

he has an army before which armies scatter.

All the kings of the Rūm requite him jizya

unwillingly, perforce, out of hand in humiliation."

Poem in praise of Harun al-Rashid's 806 entrada against Byzantium[82]

Wishing to emphasize his piety and office as the leader of the Muslim community, Caliph Harun al-Rashid (r. 786–809) in detail was the nearly energetic of the early on Abbasid rulers in his pursuit of warfare against Byzantium: he established his seat at Raqqa shut to the frontier, he complemented the thughur in 786 by forming a 2d defensive line along northern Syria, the al-'Awasim, and was reputed to be spending alternating years leading the Hajj and leading a campaign into Anatolia, including the largest expedition assembled nether the Abbasids, in 806.[83] [84]

Continuing a trend started by his immediate predecessors, his reign also saw the evolution of far more regular contacts between the Abbasid court and Byzantium, with the exchange of embassies and letters being far more than mutual than under the Umayyad rulers. Despite Harun's hostility, "the existence of embassies is a sign that the Abbasids accepted that the Byzantine empire was a power with which they had to bargain on equal terms" (Kennedy).[85] [86]

Civil war occurred in the Byzantine Empire, often with Arab support. With the support of Caliph Al-Ma'mun, Arabs nether the leadership of Thomas the Slav invaded, so that within a matter of months, only two themata in Asia Pocket-size remained loyal to Emperor Michael Two.[87] When the Arabs captured Thessalonica, the Empire's 2nd largest urban center, it was rapidly re-captured by the Byzantines.[87] Thomas'due south 821 siege of Constantinople did not get past the metropolis walls, and he was forced to retreat.[87]

The Arabs did not relinquish their designs on Asia Pocket-sized and in 838 began another invasion, sacking the city of Amorion.

Sicily, Italy and Crete [edit]

While a relative equilibrium reigned in the Due east, the situation in the western Mediterranean was irretrievably altered when the Aghlabids began their tiresome conquest of Sicily in the 820s. Using Tunisia as their launching pad, the Arabs started by conquering Palermo in 831, Messina in 842, Enna in 859, culminating in the capture of Syracuse in 878.[88]

This in turn opened upward southern Italy and the Adriatic Body of water for raids and settlement. Byzantium further suffered an important setback with the loss of Crete to a band of Andalusian exiles, who established a piratical emirate on the island and for more than a century ravaged the coasts of the hitherto secure Aegean Body of water.[ commendation needed ]

Byzantine resurgence, 863–11th century [edit]

A map of the Byzantine-Arab naval competition in the Mediterranean, seventh to 11th centuries

In 863 during the reign of Michael Iii, the Byzantine general Petronas defeated and routed an Arab invasion force under the command of Umar al-Aqta at the Battle of Lalakaon inflicting heavy casualties and removing the Emirate of Melitene as a serious military threat.[89] [ninety] Umar died in battle and the remnants of his army was annihilated in subsequent clashes, allowing the Byzantines to celebrate the victory equally revenge for the earlier Arab sacking of Amorion, while news of the defeats sparked riots in Baghdad and Samarra.[91] [90] In the following months the Byzantines successfully invaded Armenia killing the Muslim governor in Armenia Emir Ali ibn Yahya too as the Paulician leader Karbeas.[92] These Byzantines victories marked a turning betoken which ushered in a century long Byzantine offensive eastward into Muslim territory.[91]

Religious peace came with the emergence of the Macedonian dynasty in 867, as well as a strong and unified Byzantine leadership;[93] while the Abassid empire had splintered into many factions after 861. Basil I revived the Byzantine Empire into a regional power, during a period of territorial expansion, making the Empire the strongest ability in Europe, with an ecclesiastical policy marked by good relations with Rome. Basil allied with the Holy Roman Emperor Louis 2 against the Arabs, and his fleet cleared the Adriatic Sea of their raids.[94]

With Byzantine help, Louis Ii captured Bari from the Arabs in 871. The city became Byzantine territory in 876. The Byzantine position on Sicily deteriorated, and Syracuse fell to the Emirate of Sicily in 878. Catania was lost in 900, and finally the fortress of Taormina in 902. Michael of Zahumlje apparently on 10 July 926 sacked Siponto (Latin: Sipontum), which was a Byzantine town in Apulia.[94] Sicily would remain under Arab control until the Norman invasion in 1071.

Although Sicily was lost, the general Nikephoros Phokas the Elder succeeded in taking Taranto and much of Calabria in 880, forming the nucleus for the later Catepanate of Italia. The successes in the Italian Peninsula opened a new period of Byzantine domination there. Above all, the Byzantines were beginning to found a strong presence in the Mediterranean Sea, and especially the Adriatic.

Under John Kourkouas, the Byzantines conquered the emirate of Melitene, along with Theodosiopolis the strongest of the Muslim border emirates, and advanced into Armenia in the 930s; the adjacent three decades were dominated past the struggle of the Phokas clan and their dependants confronting the Hamdanid emir of Aleppo, Sayf al-Dawla. Al-Dawla was finally defeated by Nikephoros II Phokas, who conquered Cilicia and northern Syria, including the sack of Aleppo, and recovered Crete. His nephew and successor, John I Tzimiskes, pushed even further due south, nearly reaching Jerusalem, but his expiry in 976 concluded Byzantine expansion towards Palestine.

After putting an end to the internal strife, Basil II launched a counter-entrada against the Arabs in 995. The Byzantine ceremonious wars had weakened the Empire's position in the eastward, and the gains of Nikephoros II Phokas and John I Tzimiskes came close to existence lost, with Aleppo besieged and Antioch under threat. Basil won several battles in Syria, relieving Aleppo, taking over the Orontes valley, and raiding further south. Although he did not take the force to drive into Palestine and reclaim Jerusalem, his victories did restore much of Syrian arab republic to the empire – including the larger urban center of Antioch which was the seat of its eponymous Patriarch.[95]

No Byzantine emperor since Heraclius had been able to hold these lands for any length of fourth dimension, and the Empire would retain them for the next 110 years until 1078. Piers Paul Read writes that by 1025, Byzantine state "stretched from the Straits of Messina and the northern Adriatic in the west to the River Danube and Crimea in the north, and to the cities of Melitene and Edessa beyond the Euphrates in the east."[95]

Under Basil II, the Byzantines established a swath of new themata, stretching northeast from Aleppo (a Byzantine protectorate) to Manzikert. Under the Theme system of military and authoritative government, the Byzantines could raise a force at least 200,000 stiff, though in practice these were strategically placed throughout the Empire. With Basil'southward rule, the Byzantine Empire reached its greatest height in nearly 5 centuries, and indeed for the next iv centuries.[96]

Conclusion [edit]

The wars drew near to a closure when the Turks and various Mongol invaders replaced the threat of either power. From the 11th and twelfth centuries onwards, the Byzantine conflicts shifted into the Byzantine-Seljuk wars with the continuing Islamic invasion of Anatolia being taken over by the Seljuk Turks.

Afterward the defeat at the Battle of Manzikert past the Turks in 1071, the Byzantine Empire, with the assist of Western Crusaders, re-established its position in the Middle East as a major power. Meanwhile, the major Arab conflicts were in the Crusades, and later against Mongolian invasions, especially that of the Ilkhanate and Timur.

Effects [edit]

As with any state of war of such length, the drawn-out Byzantine–Arab Wars had long-lasting effects for both the Byzantine Empire and the Arab globe. The Byzantines experienced all-encompassing territorial loss. However, while the invading Arabs gained strong control in the Centre East and Africa, further conquests in Western Asia were halted. The focus of the Byzantine Empire shifted from the western reconquests of Justinian to a primarily defensive position, against the Islamic armies on its eastern borders. Without Byzantine interference in the emerging Christian states of western Europe, the situation gave a huge stimulus to feudalism and economic cocky-sufficiency.[97]

The view of modernistic historians is that one of the most important effects was the strain information technology put on the relationship between Rome and Byzantium. While fighting for survival against the Islamic armies, the Empire was no longer able to provide the protection information technology had once offered to the Papacy; worse notwithstanding, co-ordinate to Thomas Woods, the Emperors "routinely intervened in the life of the Church in areas lying conspicuously beyond the country's competence".[98] The Iconoclast controversy of the 8th and ninth centuries tin be taken every bit a key cistron "which drove the Latin Church into the arms of the Franks."[74] Thus information technology has been argued that Charlemagne was an indirect product of Muhammad:

- "The Frankish Empire would probably never accept existed without Islam, and Charlemagne without Mahomet would be inconceivable."[99]

The Holy Roman Empire of Charlemagne's successors would later come to the assistance of the Byzantines under Louis Two and during the Crusades, simply relations between the two empires would be strained; based on the Salerno Chronicle, nosotros know the Emperor Basil had sent an angry letter to his western analogue, reprimanding him for usurping the championship of emperor.[100] He argued that the Frankish rulers were simple reges, and that each nation has its own title for the ruler, whereas the imperial title suited only the ruler of the Eastern Romans, Basil himself.[ citation needed ]

Historiography and other sources [edit]

The 12th-century William of Tyre (right), an important commentator on the Crusades and the last stage of the Byzantine-Arab Wars

Walter Emil Kaegi states that extant Arabic sources have been given much scholarly attention for problems of obscurities and contradictions. However, he points out that Byzantine sources are also problematic, such as the chronicles of Theophanes and Nicephorus and those written in Syriac, which are short and terse while the of import question of their sources and their apply of sources remains unresolved. Kaegi concludes that scholars must besides subject the Byzantine tradition to critical scrutiny, as it "contains bias and cannot serve as an objective standard against which all Muslim sources may be confidently checked".[101]

Among the few Latin sources of interest are the 7th-century history of Fredegarius, and two 8th-century Castilian chronicles, all of which draw on some Byzantine and oriental historical traditions.[102] As far every bit Byzantine military action against the initial Muslim invasions, Kaegi asserts that "Byzantine traditions ... endeavor to deflect criticism of the Byzantine debacle from Heraclius to other persons, groups, and things".[103]

The range of non-historical Byzantine sources is vast: they range from papyri to sermons (most notable those of Sophronius and Anastasius Sinaita), poetry (specially that of Sophronius and George of Pisidia) including the Acritic songs, correspondence often of a patristic provenance, apologetical treatises, apocalypses, hagiography, military manuals (in detail the Strategikon of Maurice from the beginning of the seventh century), and other non-literary sources, such every bit epigraphy, archeology, and numismatics. None of these sources contains a coherent business relationship of any of the campaigns and conquests of the Muslim armies, simply some do contain invaluable details that survive nowhere else.[104]

See besides [edit]

- Aegyptus (Roman province)

- Boxing of Tours

- Byzantine–Ottoman Wars

- Byzantine–Seljuk wars

- Early Muslim conquests

- Spread of Islam

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b The Empire's levies included Christian Armenians, Arab Ghassanids, Mardaites, Slavs, and Rus'.

- ^ Politico-religious events (such equally the outbreak of Monothelitism, which disappointed both the Monophysites and the Chalcedonians) had sharpened the differences between the Byzantines and the Syrians. Also the high taxes, the power of the landowners over the peasants and the participation in the long and exhaustive wars with the Persians were some of the reasons why the Syrians welcomed the alter.[17]

- ^ Equally recorded by Al-Baladhuri. Michael the Syrian records simply the phrase "Peace unto thee, O Syrian arab republic".[22] George Ostrogorsky describes the impact that the loss of Syrian arab republic had on Heraclius with the post-obit words: "His life's work collapsed earlier his eyes. The heroic struggle against Persia seemed to be utterly wasted, for his victories here had only prepared the way for the Arab conquest [...] This cruel plow of fortune bankrupt the anile Emperor both in spirit and in trunk.[23]

- ^ As Steven Runciman describes the event: "On a February day in the year AD 638, the Caliph Omar [Umar] entered Jerusalem along with a white camel which was ride by his slave. He was dressed in worn, filthy robes, and the army that followed him was rough and unkempt; but its subject was perfect. At his side rode the Patriarch Sophronius as chief magistrate of the surrendered metropolis. Omar rode direct to the site of the Temple of Solomon, whence his friend Mahomet [Muhammed] had ascended into Heaven. Watching him stand in that location, the Patriarch remembered the words of Christ and murmured through his tears: 'Behold the anathema of pathos, spoken of by Daniel the prophet.'"[25]

- ^ Hugh N. Kennedy notes that "the Muslim conquest of Syria does not seem to take been actively opposed by the towns, but it is striking that Antioch put up so little resistance.[26]

- ^ The Arab leadership realized early that to extend their conquests they would need a armada. The Byzantine navy was commencement decisively defeated past the Arabs at a battle in 655 off the Lycian coast, when information technology was nevertheless the virtually powerful in the Mediterranean. Theophanes the Confessor reported the loss of Rhodes while recounting the sale of the centuries-old remains of the Colossus for scrap in 655.[35]

References [edit]

Citations [edit]

- ^ "Ghassan." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2006. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 18 October 2006 [one]

- ^ a b Edward Gibbon (1788). The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, vol. 5.

- ^ a b Akram 2004, p. 425

- ^ Crawford 2013, p. 149.

- ^ Akram 2004 Chapter 36

- ^ Kaegi, Walter Eastward. Byzantium and the early Islamic conquests. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Printing, 1992. pp. ninety–93. ISBN 0-521-41172-half-dozen. Al-Tabari, p. 108. al-Baladhuri, pp. 167–68. Theophanes, p. 37.

- ^ Shaw, Jeffrey M.; Demy, Timothy J. (2017). State of war and Religion: An Encyclopedia of Organized religion and Conflict [3 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 201. ISBN9781610695176 . Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- ^ a b Treadgold (1997), pp. 346–347

- ^ A. Palmer (with contributions from S. Brock and R. One thousand. Hoyland), The 7th Century in the W-Syrian Chronicles Including 2 Seventh-Century Syriac Apocalyptic Texts, 1993, op. cit., pp. 18–nineteen; Besides see R. G. Hoyland, Seeing Islam As Others Saw It: A Survey And Evaluation of Christian, Jewish And Zoroastrian Writings on Early on Islam, 1997, op. cit., p. 119 and p. 120:

"On Friday, 4 Feb, at the ninth hour, at that place was a battle between the Romans and the Arabs of Mụhmet (Muhammad) in Palestine twelve miles due east of Gaza. The Romans fled, leaving behind the patrician Yarden, whom the Arabs killed. Some 4000 poor villagers of Palestine were killed there, Christians, Jews and Samaritans. The Arabs ravaged the whole region." - ^ Theophanes, Relate, 317–327

* Greatrex–Lieu (2002), II, 217–227; Haldon (1997), 46; Baynes (1912), passim; Speck (1984), 178 - ^ Foss (1975), 746–47; Howard-Johnston (2006), xv

- ^ Liska (1998), 170

- ^ Kaegi (1995), 66

- ^ Nicolle (1994), 14

- ^ "Muhammad", Belatedly Artifact; Butler (2007), 145

- ^ a b c Kaegi (1995), 67

- ^ Read (2001), 50–51; Sahas (1972), 23

- ^ Nicolle (1994), 47–49

- ^ a b Kaegi (1995), 112

- ^ Nicolle (1994), 45

- ^ "Cyberspace History Sourcebooks Project". Archived from the original on xi October 2013. Retrieved seven February 2016.

- ^ Al-Baladhuri, The Battle of the Yarmuk (636) and after Archived 11 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine; Michael the Syrian, Chronicle, Two, 424

* Sahas (1972), 19–20 - ^ Quoted past Sahas (1972), 20 (note 1)

- ^ Zonaras, Annales, CXXXIV, 1288

* Sahas (1972), 20 - ^ Runciman (1953), i, three

- ^ Kennedy (2001b), 611; Kennedy (2006), 87

- ^ Kennedy (1998), 62

- ^ Butler (2007), 427–428

- ^ Davies (1996), 245, 252

- ^ a b Read (2001), 51

- ^ Haldon (1999), 167; Tathakopoulos (2004), 318

- ^ Butler (2007), 465–483

- ^ Al-Baladhuri, The Boxing of the Yarmuk (636) and after Archived 11 Oct 2013 at the Wayback Machine

* Sahas (1972), 23 - ^ Treadgold (1997), 312

- ^ Theophanes, Chronicle, 645–646

* Haldon (1990), 55 - ^ Fage–Tordoff, 153–154

- ^ Norwich (1990), 334

- ^ Volition Durant, The History of Civilization: Part IV—The Age of Faith. 1950. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-671-01200-two

- ^ The Islamic World to 1600: Umayyad Territorial Expansion.

- ^ Clark, Desmond J.; Roland Anthony Oliver; J. D. Fage; A. D. Roberts (1978) [1975]. The Cambridge History of Africa. Cambridge University Printing. p. 637. ISBN0-521-21592-7.

- ^ a b Edward Gibbon, History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Chapter 51. Archived 21 July 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Luis Garcia de Valdeavellano, Historia de España. 1968. Madrid: Alianza.

- Quotes translated from the Spanish by Helen R. Lane in Count Julian by Juan Goytisolo. 1974. New York: The Viking Press, Inc. ISBN 0-670-24407-4

- ^ Kaegi (1995), pp. 236–244

- ^ a b Kennedy (2004) p. 120

- ^ European Naval and Maritime History, 300–1500 By Archibald Ross Lewis, Timothy J. Runyan Page 24 [2]

- ^ History of the Jihad Past Leonard Michael Kroll Page 123

- ^ A History of Byzantium By Timothy E. Gregory folio 183

- ^ Prophets and Princes: Saudi Arabia from Muhammad to the Present Past Marking Weston Page 61 [3]

- ^ The Medieval Siege Past Jim Bradbury Page 11

- ^ Pryor & Jeffreys (2006), p. 25

- ^ Treadgold (1997), pp. 313–314

- ^ Kennedy (2004) pp. 120, 122

- ^ Kaegi (1995), pp. 246–247

- ^ a b El-Cheikh (2004), pp. 83–84

- ^ Treadgold (1997), pp. 314–318

- ^ Treadgold (1997), pp. 318–324

- ^ Treadgold (1997), pp. 325–327

- ^ The Walls of Constantinople, Advertizing 324–1453 Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 1-84176-759-X.

- ^ Karen Armstrong: Islam: A Short History. New York, NY, USA: The Modern Library, 2002, 2004 ISBN 0-8129-6618-Ten

- ^ a b c Davies (1996), 245

- ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. xv (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 602.

- ^ Treadgold (1997), pp. 337–345

- ^ Treadgold (1997), p. 347

- ^ Treadgold (1997), pp. 347–349

- ^ a b Blankinship (1994), pp. 117–119

- ^ Treadgold (1997), pp. 349ff.

- ^ Kennedy (2004), pp. 143, 275

- ^ El-Cheikh (2004), p. 83

- ^ Blankinship (1994), pp. 119–121, 162–163

- ^ Volcanism on Santorini / eruptive history

- ^ a b Treadgold (1997), pp. 350–353

- ^ a b Whittow (1996), pp. 139–142

- ^ Europe: A History, p. 273. Oxford: Oxford University Press 1996. ISBN 0-nineteen-820171-0

- ^ a b Europe: A History, p246. Oxford: Oxford Academy Press 1996. ISBN 0-xix-820171-0

- ^ Blankinship (1994), pp. 20, 168–169, 200

- ^ Treadgold (1997), pp. 354–355

- ^ El Hibri (2011), p. 302

- ^ a b El Hibri (2011), pp. 278–279

- ^ a b Kennedy (2001), pp. 105–106

- ^ El Hibri (2011), p. 279

- ^ Kennedy (2001), p. 106

- ^ El-Cheikh (2004), p. 90

- ^ El-Cheikh (2004), pp. 89–90

- ^ Kennedy (2004), pp. 143–144

- ^ cf. El-Cheikh (2004), pp. 90ff.

- ^ Kennedy (2004), p. 146

- ^ a b c John Julius Norwich (1998). A Short History of Byzantium. Penguin. ISBN0-fourteen-025960-0.

- ^ Kettani, Houssain (eight November 2019). The Globe Muslim Population: Spatial and Temporal Analyses. CRC Press. ISBN978-0-429-74925-4.

- ^ DK (16 April 2012). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Warfare: From Ancient Egypt to Iraq. DK Publishing. p. 375. ISBN978-i-4654-0373-5.

- ^ a b Georgios Theotokis; Dimitrios Sidiropoulos (26 April 2021). Byzantine Military Rhetoric in the Ninth Century: A Translation of the Anonymi Byzantini Rhetorica Militaris. Taylor & Francis. p. 13. ISBN978-ane-00-038999-9.

- ^ a b Mark Whittow (1996). The Making of Byzantium, 600-1025. Academy of California Printing. p. 311. ISBN978-0-520-20496-half-dozen.

- ^ Warren T. Treadgold (October 1997). A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford University Press. p. 452. ISBN978-0-8047-2630-half-dozen.

- ^ Europe: A History. Oxford: Oxford University Printing 1996. ISBN 0-xix-820171-0

- ^ a b Rački, Odlomci iz državnoga práva hrvatskoga za narodne dynastie:, p. fifteen

- ^ a b Read (2001), 65–66

- ^ See map depicting Byzantine territories from the 11th century on; Europe: A History, p. 1237. Oxford: Oxford University Press 1996. ISBN 0-19-820171-0

- ^ Europe: A History, p 257. Oxford: Oxford Academy Printing 1996. ISBN 0-19-820171-0

- ^ Thomas Woods, How the Cosmic Church Built Western Civilization, (Washington, DC: Regenery, 2005), ISBN 0-89526-038-vii

- ^ Pirenne, Henri

- Mediaeval Cities: Their Origins and the Rivival of Trade (Princeton, NJ, 1925). ISBN 0-691-00760-8

- See also Mohammed and Charlemagne (London 1939) Dover Publications (2001). ISBN 0-486-42011-6.

- ^ Dolger F., Regesten der Kaiserurkunden des ostromischen Reiches. I, p 59, №487. Berlin, 1924.

- ^ Kaegi (1995), ii–3

- ^ Kaegi (1995), 2

- ^ Kaegi (1995), 4–v

- ^ Kaegi (1995), 5–six

Sources [edit]

- Primary sources

- Ahmad ibn Yahya al-Baladhuri. Futuh al-Buldan. Come across a translated extract ("The Battle of Yarmouk and after") in Medieval Sources.

- Michael the Syrian (1899). Chronique de Michel le Syrien Patriarche Jacobite d'Antioche (in French and Syriac). Translated by J.–B. Chabot. Paris.

- Theophanes the Confessor. Relate. Come across original text in Documenta Catholica Omnia (PDF).

- Zonaras, Joannes, Annales. Run into the original text in Patrologia Graeca.

- Secondary sources

- Baynes, Norman H. (1912). "The restoration of the Cantankerous at Jerusalem". The English Historical Review. 27 (106): 287–299. doi:10.1093/ehr/XXVII.CVI.287.

- Akram, A.I. (2004), The Sword of Allah: Khalid bin al-Waleed – His Life and Campaigns, third edition, ISBN0-19-597714-9

- Blankinship, Khalid Yahya (1994). The End of the Jihâd Land: The Reign of Hishām ibn ʻAbd al-Malik and the Collapse of the Umayyads. Albany, New York: Country University of New York Press. ISBN978-0-7914-1827-7.

- Brooks, E. West. (1923). "Chapter V. (A) The Struggle with the Saracens (717–867)". The Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. IV: The Eastern Roman Empire (717–1453). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 119–138.

- Butler, Alfred J. (2007). The Arab Conquest of Egypt – And the Last Thirty Years of the Roman. Read Books. ISBN978-ane-4067-5238-0.

- Crawford, Peter (2013). The War of the Iii Gods: Romans, Persians and the Ascension of Islam. Pen and Sword.

- Davies, Norman (1996). "The Nativity of Europe". Europe . Oxford University Press. ISBN0-19-820171-0.

- El-Cheikh, Nadia Maria (2004). Byzantium viewed by the Arabs. Harvard Center of Middle Eastern Studies. ISBN978-0-932885-30-2.

- El-Hibri, Tayeb (2010). "The empire in Iraq, 763–861". In Robinson, Chase F. (ed.). The New Cambridge History of Islam, Volume 1: The Formation of the Islamic Globe, Sixth to Eleventh Centuries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 269–304. ISBN978-0-521-83823-8.

- Foss, Clive (1975). "The Persians in Asia Minor and the End of Artifact". The English Historical Review. 90: 721–47. doi:10.1093/ehr/XC.CCCLVII.721.

- Greatrex, Geoffrey; Lieu, Samuel N. C. (2002). The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Farsi Wars (Part Two, 363–630 AD). Routledge. ISBN0-415-14687-nine.

- Haldon, John (1997). "The East Roman World: the Politics of Survival". Byzantium in the Seventh Century: the Transformation of a Culture. Cambridge. ISBN0-521-31917-Ten.

- Haldon, John (1999). "The Ground forces at Wars: Campaigns". Warfare, Country and Society in the Byzantine World, 565–1204. London: UCL Press. ISBN1-85728-495-X.

- Howard-Johnston, James (2006). Eastward Rome, Sasanian Persia And the End of Antiquity: Historiographical And Historical Studies. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN0-86078-992-6.

- Kaegi, Walter Emil (1995). Byzantium and the early Islamic conquests. Cambridge University Printing. ISBN0-521-48455-3.

- Kennedy, Hugh (1998). "Egypt as a Province in the Islamic Caliphate, 641–868". In Daly, M.W.; Petry, Calf. F. (eds.). The Cambridge History of Arab republic of egypt. Cambridge University Printing. ISBN0-521-47137-0.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2001). The Armies of the Caliphs: Military and Society in the Early on Islamic State. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN0-415-25093-5.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2000). "Syria, Palestine, and Mesopotamia". In Cameron, Averil; Ward-Perkins, Bryan; Whitby, Michael (eds.). The Cambridge Aboriginal History, Book 14: Late Antiquity: Empire and Successors, A.D. 425–600. Cambridge: Cambridge University Printing. ISBN9780521325912.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2016). The Prophet and the Historic period of the Caliphates: The Islamic Well-nigh Eastward from the sixth to the 11th Century (second ed.). Oxford and New York: Routledge. ISBN978-1-138-78761-2.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2006). "Antioch: from Byzantium to Islam". The Byzantine and Early on Islamic Nearly East. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN0-7546-5909-7.

- Liska, George (1998). "Project contra Prediction: Culling Futures and Options". Expanding Realism: The Historical Dimension of World Politics. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN0-8476-8680-ix.

- Warren Bowersock, Glen; Brown, Peter; Robert Lamont Brownish, Peter; Grabar, Oleg, eds. (1999). "Muhammad". Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Postclassical World. Harvard University Press. ISBN0-674-51173-5.

- Nicolle, Davis (1994). Yarmuk AD 636. Osprey Publishing. ISBN1-85532-414-8.

- Norwich, John Julius (1990). Byzantium: The Early Centuries. Penguin Books. ISBN978-0-fourteen-011447-eight.

- Omrčanin, Ivo (1984). Armed services history of Republic of croatia. Dorrance. ISBN978-0-8059-2893-8.

- Pryor, John H.; Jeffreys, Elizabeth One thousand. (2006). The Age of the ΔΡΟΜΩΝ: The Byzantine Navy ca. 500–1204. Brill Bookish Publishers. ISBN978-90-04-15197-0.

- Rački, Franjo (1861). Odlomci iz državnoga práva hrvatskoga za narodne dynastie (in Croation). F. Klemma.

- Read, Piers Paul (1999). The Templars. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, Orion Publishing Group. ISBN0-297-84267-6.

- Runciman, Steven (1987). A History of the Crusades. Cambridge University Press. ISBN0-521-34770-X.

- Sahas, Daniel J. (1972). "Historical Considerations". John of Damascus on Islam. BRILL. ISBN90-04-03495-1.

- Speck, Paul (1984). "Ikonoklasmus und die Anfänge der Makedonischen Renaissance". Varia 1 (Poikila Byzantina 4). Rudolf Halbelt. pp. 175–210.

- Stathakopoulos, Dionysios (2004). Dearth and Pestilence in the Belatedly Roman and Early on Byzantine Empire. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN0-7546-3021-8.

- Treadgold, Warren (1997). A History of the Byzantine Land and Society. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN0-8047-2630-ii.

- Vasiliev, A.A. (1923), "Chapter V. (B) The Struggle with the Saracens (867–1057)", The Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. Four: The Eastern Roman Empire (717–1453), Cambridge University Press, pp. 138–150

- Vasiliev, A.A. (1935), Byzance et les Arabes, Tome I: La Dynastie d'Amorium (820–867) (in French), French ed.: Henri Grégoire, Marius Canard, Brussels: Éditions de 50'Institut de Philologie et d'Histoire Orientales

- Vasiliev, A.A. (1968), Byzance et les Arabes, Tome II, 1ére partie: Les relations politiques de Byzance et des Arabes à L'époque de la dynastie macédonienne (867–959) (in French), French ed.: Henri Grégoire, Marius Canard, Brussels: Éditions de l'Institut de Philologie et d'Histoire Orientales

Further reading [edit]

- Kennedy, Hugh North. (2006). The Byzantine And Early Islamic Near Due east. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN0-7546-5909-7.

External links [edit]

-

Media related to Arab–Byzantine wars at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Arab–Byzantine wars at Wikimedia Commons

Unit 3 Reading Guide Byzantine Empire, Islam, and Africa

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arab%E2%80%93Byzantine_wars

0 Response to "Unit 3 Reading Guide Byzantine Empire, Islam, and Africa"

Post a Comment